Writing and AI

Information and materials for students and lecturers

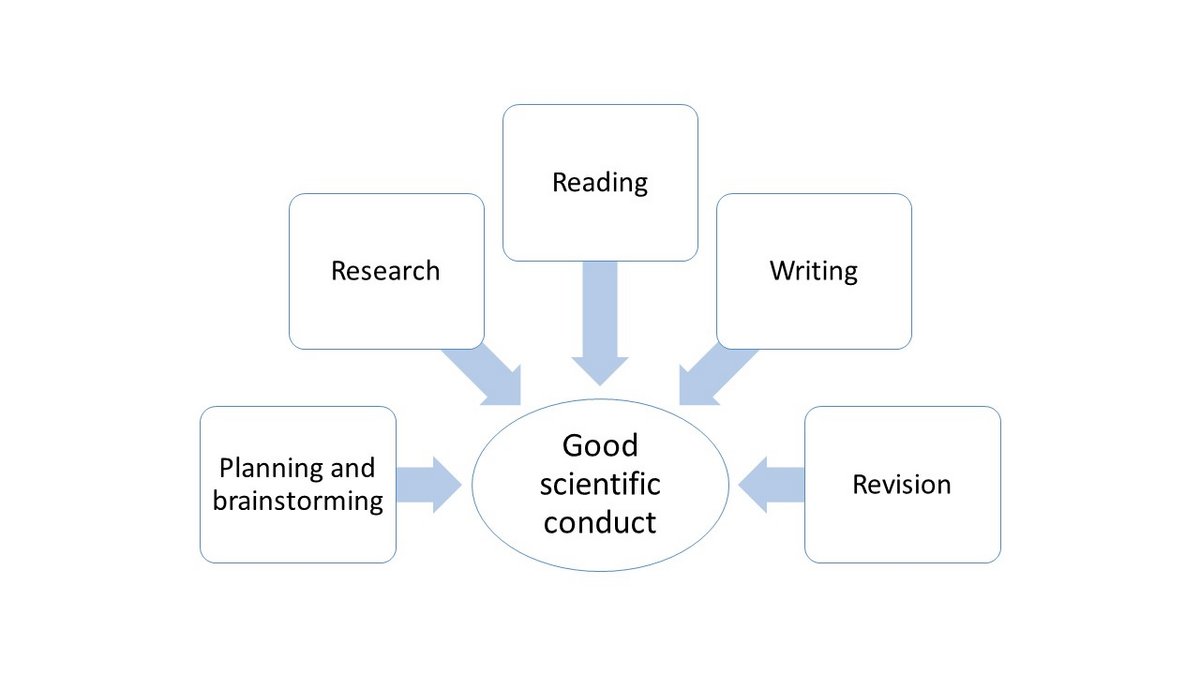

More and more often, AI tools are integrated into writing processes. This can help relieve cognitive strain – but only if writers are aware of which tasks they can outsource, when and where they need to critically evaluate output and that they themselves must always assume responsibility for the resulting text parts.

The steps outlined below encourage and demand the students’ own effort. In princinple, AI tools can be used well in every step, but they must be critically reflected upon and adapted to the context. The use and handling of AI tools for academic writing is part of our teaching consultations and teaching units. We work within the framework of the university’s current guidelines.

Planning and Brainstorming

AI tools can help with brainstorming – just like a conversation among peers can. However, the decision about and responsibility for which ideas to pursue remains with the students.

The more precisely I can sy what I want, the more focused the output of an AI tool will be. Nevertheless, this first draft will still need further iterations. AI and humans can work well together here, and prompting can be an opportunity to become aware of your own topic. The role, context and readers of a text influence the result.

Students who work well in this phase can set up successful research and data collection and thus are able to develop a better focus of their topic.

Literature Research

AI tools have the great advantage that they allow interactions in natural language. However, they are no substitute for a thorough search strategy. The KIM is the right point of call for students and lecturers who have research questions.

The decision as to which approach to choose, which research strategy to pursue and which results to continue working with is clearly a human responsibility. Questions posed by AI tools are not geared towards your own research interests or the context of a specific course. Nevertheless, they can be helpful in sharpening your own perspective.

Reading

There are a number of AI tools that support the reading of texts. The ability to ask text-related questions and have terms explained to you outside of a course can support your learning. AI tools can take on the role of a tutor who patiently answers all your questions and helps with exam preparation. Here too, however, it is important to keep in mind that AI tools do not “know” what they are saying, even if it sounds like they do.

In this phase, it makes sense to formulate your own ideas and perspectives, i.e. to start writing and thinking for yourself. The small and informal texts that are created in the process are an important aid and, in case there is ever any doubt about how a text originated, can also serve as proof of how you have approached the topic yourself.

Drafting

AI tools such as ChatGPT are particularly good at producing convincing-sounding text in which grammar and spelling are (almost) free of errors. This makes the resulting texts sound much more finished than they actually are. The temptation to outsource drafting to an AI is particularly great for inexperienced writers. And inexperienced writers find it very difficult to really read and critique finished-sounding texts.

It is better if you try to write a first draft yourself and only let the AI help you in revising it. You can use the strengths of AI tools by, for example, having them generate a selection of phrases, sentences, transitions etc. and then to continue working with them.

Lecturers can let an AI generate a selection of outputs and discuss these with the students during class. In this way, they can work out together what is good about an output and what is not, and the joint discussion can lead to a more in-depth understanding.

Revising

During revision, texts that we have written in order to understand what we want to say (Judith Wolfsberger calls them „I-texts“) become texts that are directed at readers („you-texts“).

A good text has a logical sequence, a golden thread. This is precisely where AI texts that have been plucked from the tool without further iteration do not perform well: they do not build up an argument and do not follow a stringent line. Rather, they gather and name aspects side by side. If the aim is to present a certain number of ideas in order to score points (sometimes this is the case in exams) and their sequence is irrelevant, this can work.

Academic texts, however, are assessed according to whether they build a solid argument that works within the framework of a particular discipline. At the university, there is usually also the aspect that they have to make sense within the context of a specific course.

AI generated texts may sound very good and authoritative, but they can only imitate this scientific argumentation and only land hits by chance. Writers therefore have to think about the structure of their own texts themselves.

However, what AI tools are good at is formulating. Use them exactly for this purpose, and not just the ubiquitous ChatGPT but also tools such as DeepLWrite or Language Tool, which have been developed precisely for making alternative linguistic suggestions instead of intervening in the content (and writing nonsense in the process).

Materials for lecturers

- Typical weaknesses in AI texts (PDF, 125 KB)

- Exercise on bias in AI generated texts

- KI in der Lehre an der Uni Konstanz

- KI Campus Sprachassistenzen Hochschullehre

- Beiträge des Virtuellen Kompetenzzentrums

- Beiträge der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Hochschuldidaktik

- KI:edu.nrw - Didaktik, Ethik und Technik von Learning Analytics und KI in der Hochschulbildung